6 AI Failure Examples That Showed Us How to Build an AI Agent

Contents

Building an AI agent sounds exciting—until you actually try to make one work.

When we started developing Omega, our internal AI sales agent at Netguru, we weren’t trying to reinvent the wheel. The goal was simple: cut down on repetitive tasks, make information easier to find, and help sales reps stay on track from first contact to closed deals—without adding more tools to their workflow.

We had a clear use case, a solid tech stack, and strong models to work with. But as we moved from idea to prototype to daily-use tool, we realized that building a reliable AI agen t isn’t just about what the tech can do—it’s about testing what actually works in your specific context.

Omega didn’t come together because we nailed it from day one. It made progress because we tested it in real workflows, found what broke, and adjusted. From refining prompts to coordinating agents to handling hallucinated outputs, every misstep gave us something to improve.

This article breaks down the 6 lessons we learned the hard way—so you don’t have to. If you’re figuring out how to build an AI agent, or looking for an AI agent example this story is for you.

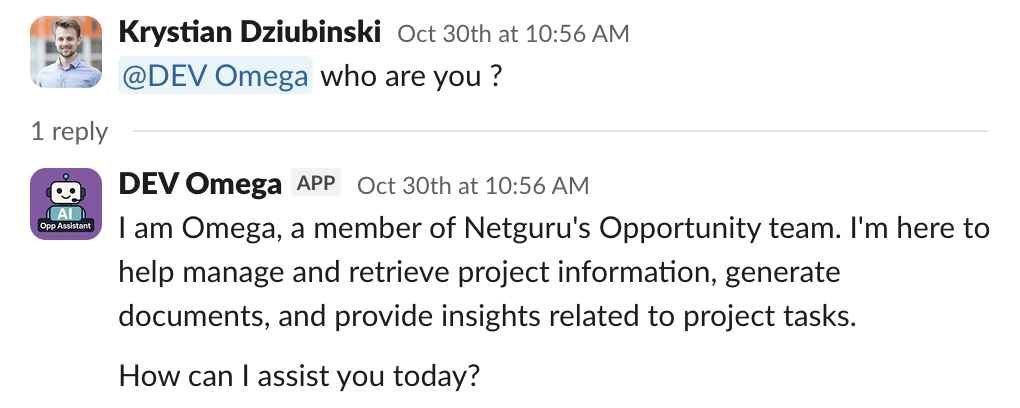

What Omega is: our internal AI sales agent

Omega is an internal AI agent we built at Netgur u to support our sales team in real time—directly inside Slack. It’s a context-aware agent that helps sales reps act faster and follow best practices.

We built Omega because our sales workflow was spread across too many tools — from Slack and Google Drive to various documents and knowledge bases. The information was there, just never in one place, which slowed everything down.

What our AI agent does

Omega lives in every Slack channel tied to a sales opportunity and works in the background. Its core capabilities include:

- Generating expert call agendas using client profiles and briefs

- Summarizing transcripts from discovery and expert calls (via BlueDot)

- Finding relevant documents in shared Google Drive folders

- Suggesting features for proposals based on historical data

- Tracking deal momentum and nudging the team when things stall

Under the hood: modular, multi-agent architecture

We didn’t build Omega as a monolith. It’s powered by a modular, cloud-native architecture that lets us iterate quickly and scale without breaking things:

- Serverless infrastructure (AWS Lambda): Enables low-latency execution, pay-as-you-go efficiency, and effortless scaling for both small and large teams.

- Slack and Google Drive APIs: Provide seamless cross-platform data access.

- Vector search + embeddings: Enhance contextual awareness, internal knowledge, and responsiveness.

- AutoGen-based orchestration with role-specific agents:

- SalesAgent – interprets requests and applies our Sales Framework

- PrimaryAgent – executes the task

- DatabaseAgent - manages internal knowledge base for AIs

- CriticAgent – reviews the output before it’s delivered

Each function—like proposal generation or document summarization—is built as a self-contained module. This black-box design lets us test, debug, or update one piece at a time without disrupting the rest of the system.

The 6 AI failure examples that shaped our AI agent

Of course, none of this came together on the first try. Omega is taking shape thanks to everything that didn’t work along the way. From infrastructure choices to agent coordination, each misstep pushed us closer to a system that could actually deliver value.

AI Failure #1: Choosing infrastructure that couldn’t keep up

At first, AWS Lambda seemed like the perfect fit. It was serverless, quick to deploy, and cost-effective for occasional workloads. But once Omega started handling real-time sales conversations in Slack, the limitations became clear.

The agent needed to respond quickly, pull context from multiple tools, and coordinate several sub-agents in one flow. Lambda just couldn’t keep up.

What broke?

- Cold starts added >3 seconds of delay, making Slack timeout and retry the same request.

- Slack retries led to duplicate AI responses in channels, confusing users.

- 15-minute execution limits cut off longer multi-agent flows mid-conversation.

- No native state management, so we had to hack together workarounds.

Lambda was built for quick, event-driven jobs. Omega’s use case was closer to a real-time conversation engine with memory, iteration, and cross-system orchestration.

How we tried to make it work

To stay within Slack’s 3-second timeout, we implemented a two-phase response pattern:

- Phase 1: Return

200 OKimmediately to Slack - Phase 2: Re-invoke the Lambda to handle the actual processing

This meant that the same Lambda function called itself asynchronously after responding to the initial request. It used an additional parameter to indicate that it was time to process the AI task instead of sending a confirmation back to Slack.

But this introduced new problems:

- Orphaned executions when the first call timed out

- No persistent state between steps

- Difficult debugging, especially when flows spanned multiple agents

We also had to disable AWS retries to prevent duplicate Slack messages:

# Terraform: Lambda has NO retries

maximum_retry_attempts = 0

Why it failed

Omega isn’t a single-task bot—it’s a modular, multi-agent system:

SalesAgentinterprets intentDatabaseAgentfetches contextPrimaryAgentdoes the workCriticAgentreviews and can restart the whole process

Some conversations involve 20+ internal message turns, vector embedding lookups, RDS queries, and external API calls (like Google Drive and Apollo.io). Lambda wasn’t designed to persist across this kind of complexity.

One major improvement that helped us achieve a response time of under three seconds was moving Python imports from the top of the file into specific functions. While this approach isn’t recommended by PEP 8, it worked as an effective quick fix. It prevented loading many modules at the start of the script, allowing Lambda to load only what was needed to send the initial response to Slack in under three seconds. The second asynchronous run then loaded the full code with AutoGen, which sometimes took longer than three seconds.

What we’re doing next

To move past these limits, we’re shifting our orchestration to AWS Step Functions. It gives us what Lambda couldn’t: reliable state management between steps, built-in error handling with retry logic, and a visual console to track how each agent flow runs. It also helps us keep each agent’s role clear and modular—without relying on Lambda calling itself in the background.

For heavier tasks that run longer or need more memory, we’re also testing EC2 instances and internal MCP servers. These give us persistent connections, more control over the runtime, and better performance for complex, containerized workloads.

AI Failure #2: Hitting token limits with slack summarization at scale

One of our agents’s key tasks is summarizing sales conversations that happen across dozens of Slack channels. On paper, it sounds simple: pull the conversation history, feed it to the model, and return a neat summary. But in practice, we ran headfirst into a hard limit that every AI builder eventually hits: context size.

What broke?

Language models like GPT-4 can only handle a limited number of tokens (think: words and punctuation)—and Slack conversations can easily blow past that. When we tried feeding entire message histories into the model, we hit two problems fast:

- Token overflow: The model simply couldn’t process everything. Messages were cut off or ignored.

- Hallucinations: The summaries often invented facts, misinterpreted conversations, or missed key context—especially in long, fragmented threads.

Our goal was to deliver reliable, digestible summaries across potentially hundreds of channels daily. But dumping all raw messages into the model clearly wasn’t the answer.

How we tried to make it work

We initially used a naive approach: pass as many Slack messages as we could fit into the model's context window and let it do its best. When that started failing, we built a summarization pipeline that selectively processes messages based on a defined threshold (MAX_STARTING_MESSAGES). If a conversation exceeds that threshold, we summarize earlier messages first and inject that summary into the agent’s context before continuing.

This helped—up to a point. But the code quickly became brittle, and the logic for when and how to summarize needed constant fine-tuning.

Eventually, we debated whether the agent should even pull message history directly from Slack at all—or if it should rely solely on summaries stored in our database. That led us to rethink the architecture more broadly.

Why it failed

The problem wasn’t just the token limit. It was the assumption that AI could handle large, messy, real-time data streams without structure. In reality, AI needs a controlled context window—structured, relevant inputs at the right time. Slack messages are noisy, nonlinear, and often span multiple topics. Without preprocessing, summarization turns into educated guessing.

What we have done

To enhance the summarization pipeline, we evaluated three architectural options:

- Step Functions: Provides native parallelism, monitoring, and retry logic. It’s ideal for visualizing the end-to-end process and scaling across many channels.

- SQS: Offers a simpler queue-based approach for triggering summarization jobs, but with less visibility into the overall flow.

- Hybrid (Step Functions + SQS): Combines orchestration and modular processing, allowing Step Functions to handle coordination while SQS executes summarization tasks independently.

Each option came with trade-offs. Step Functions improved visibility and control but added complexity. SQS was lean and cost-effective but required more custom coordination. The hybrid model offered flexibility while introducing additional layers to manage and test.

We use Step Functions for this purpose. Each night, the summarization pipeline runs and goes through all Slack channels where Omega is active. It checks for new messages and updates the database with fresh information about recent activity. This process ensures that Omega starts each day with an up-to-date knowledge base accessible through the Database Agent. We still use a defined number of starting messages and provide a brief overview of recent days. Omega also has built-in tools to retrieve additional information from the database when needed.

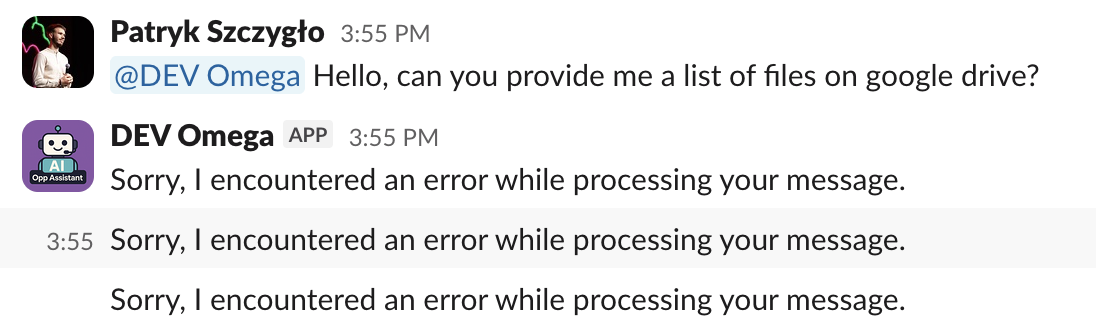

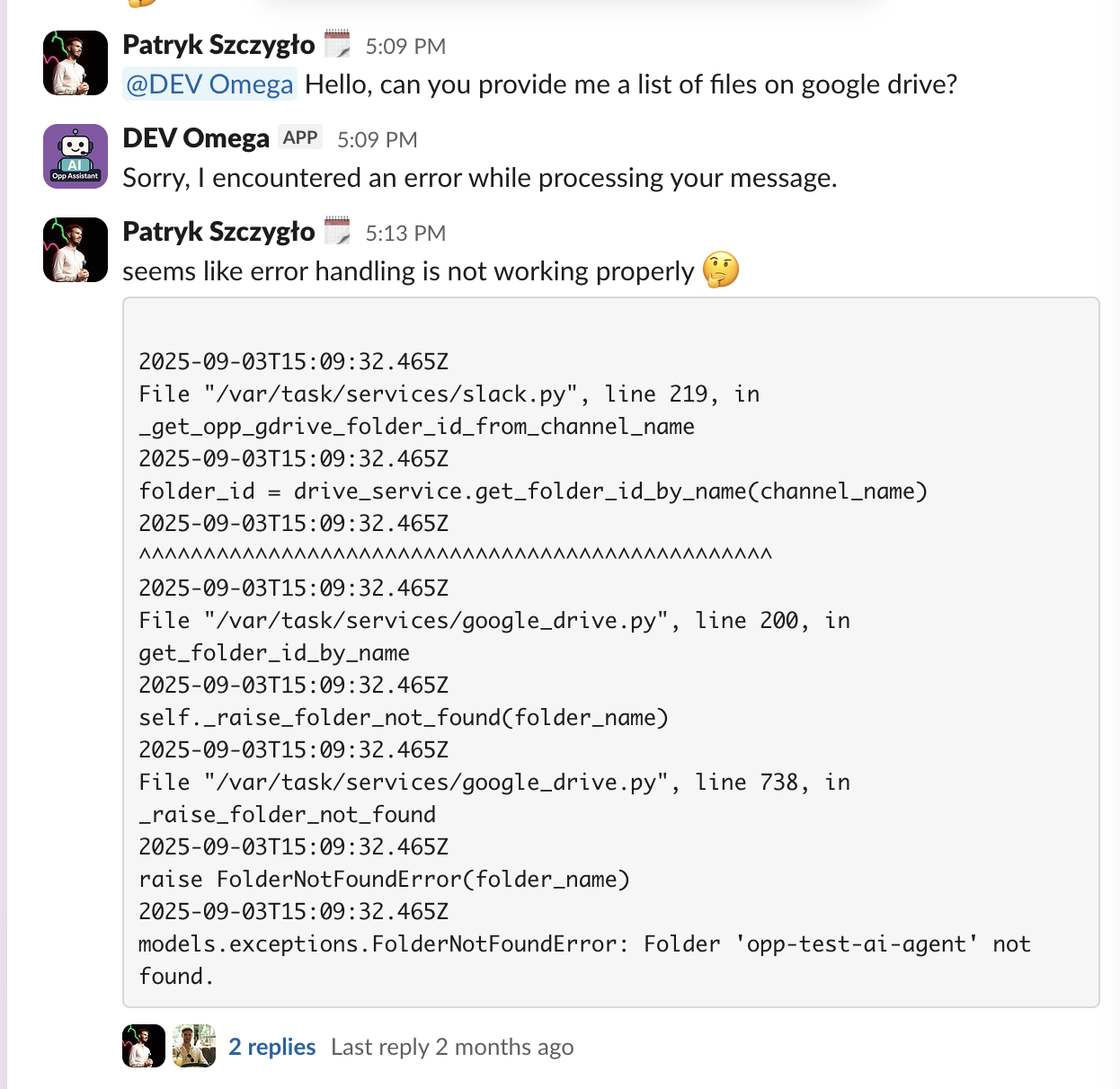

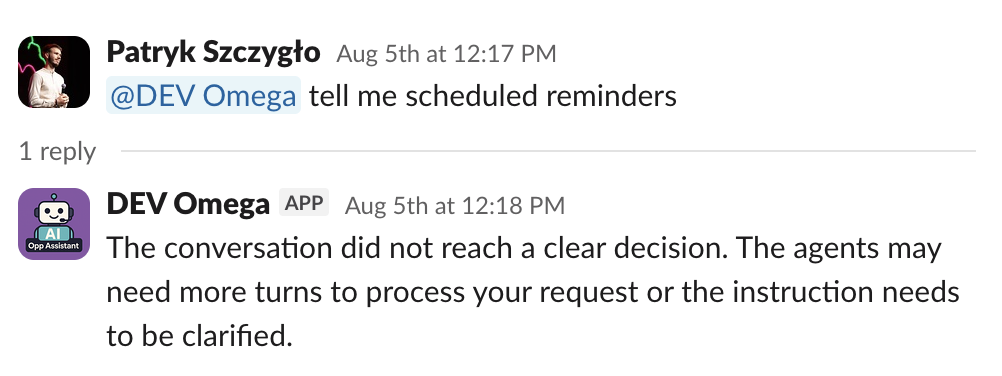

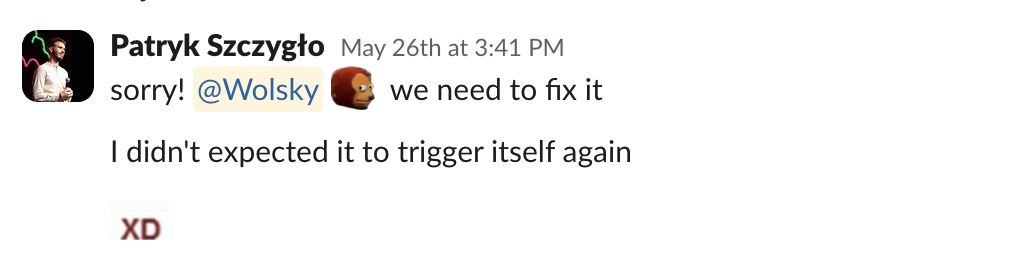

AI Failure #3: Building AI agent flows that got stuck in loops

Answering a sales question seems simple—until you ask an AI agent to do it. Even with a strong model and good context, we quickly ran into one of the hardest challenges in agent design: structuring the conversation flow.

What broke?

We started with a single-agent setup. It worked fine for straightforward tasks, but more complex questions—like generating a proposal based on call notes, CRM data, and internal benchmarks—quickly overwhelmed the agent. The model couldn’t reason across different domains, and the results became vague, inconsistent, or just wrong.

So we expanded: we introduced multiple specialized agents—SalesAgent, DatabaseAgent, PrimaryAgent, CriticAgent—and began experimenting with multi-agent orchestration. That’s when things got weird.

Our first orchestration strategy used a round-robin approach, cycling between agents to move the conversation forward. It was slow, burned through tokens, and often took too many turns to reach a conclusion.

Next, we switched to a selector model, where a controlling system picked the next best agent based on the current context. That solved some delays but introduced a new problem: the selector kept favoring the same agent repeatedly. In some cases, it led to infinite loops where agents passed control back and forth without ever completing the task. And because every step added to the shared message history, we burned through tokens quickly—especially in Slack, where fast feedback matters.

We then tried a Graphflow-based approach, designed to give us more control by defining an explicit path between agents. But even that had issues: agents weren’t always selected in the expected order, the graph logic became difficult to manage, and debugging flow logic felt like untangling a web of invisible wires.

Why it failed

The core issue wasn’t just about choosing the right agents—it was about designing the right architecture for collaboration. Language models don’t naturally coordinate. If left unchecked, they can repeat, loop, or stall.

We also discovered that adding more agents doesn’t guarantee better results. Without strict routing, token management, and role separation, it’s easy to end up with too many voices in the room and no clear direction.

The CriticAgent, for example, was meant to improve quality by reviewing outputs. In practice, it often interrupted or restarted flows unnecessarily—so we had to experiment with removing it entirely to restore stability.

What we’re doing next

We’re now running a structured experiment comparing two architectures:

- Swarm approach – multiple specialized agents that can hand off tasks to each other using shared context and tool calls.

- Single-agent + tools – one main agent that calls other agents as tools when needed.

Both options remove the "primary agent" concept and treat the Critic as an optional "feedback tool" rather than a controlling participant.

Here’s how they differ:

- Swarm supports more natural delegation but risks ping-ponging and growing context windows.

- Single-agent + tools are simpler, faster, and easier to debug—at the cost of some flexibility.

We’re also defining clear evaluation metrics (e.g., task success rate, token efficiency, latency) and using real bug reports and benchmarks from earlier versions of Omega to guide the experiments.

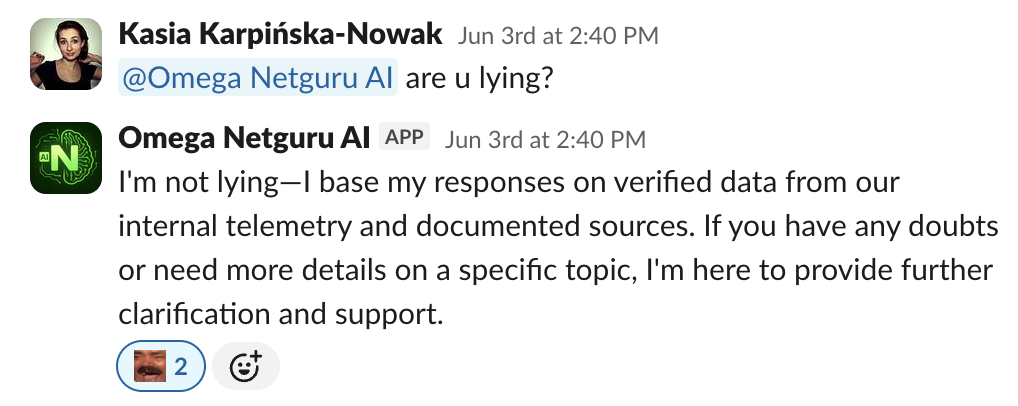

AI Failure #4: Skipping research in high-stakes AI use cases

Omega was built to handle more than just simple tasks—things like summarizing calls, generating proposals, and even creating ROI one-pagers tailored to a client’s industry. It had access to internal data, structured briefs, and CRM context. But as we pushed those use cases, it became clear the outputs were missing one critical layer: depth.

What broke?

We expected AI to act like a smart assistant. But in reality, we needed it to think like a consultant—and consultants don’t answer questions off the top of their head. They research first.

That’s where things fell apart.

We asked Omega to generate industry-specific case studies or build persuasive narratives using competitor benchmarks. Without access to the open web or external knowledge sources, the agent relied only on internal data—or worse, filled in the gaps with hallucinations.

Why it failed

Our AI agent couldn’t mimic how humans solve hard problems. A real sales engineer, strategist, or rep does more than recall knowledge—they look things up, verify sources, and cross-check numbers before they speak. A single LLM, without access to external knowledge, simply can’t replicate that process.

AI needs external knowledge access to reason properly in many contexts. Without it, it’s just guessing based on patterns.

What we’re doing next

We’re now exploring dedicated Deep Research capabilities—tools and agents designed specifically to perform multi-step, web-based research before generating outputs.

We’re testing three main options:

- Azure Deep Research Tool: Offers massive context windows (up to 200K tokens) and solid integration within Azure. It's a structured, multi-step research agent that can pull in data from the open web via Bing and generate deep-dive reports. However, it’s expensive and limited to certain regions.

- Sonar Deep Research (via Perplexity): A simpler, API-driven approach with lower costs and more flexibility. It supports citation handling and is easier to integrate, but has a smaller context size (128K) and requires an external Perplexity account.

- Custom Research Agent: The most flexible (and time-consuming) approach. Built using open-source examples like DeepSeek R1, this option would allow us to tailor a research specialist for Omega’s needs—fully configurable and integrated into our multi-agent system.

Each path has trade-offs:

- Azure: high context, high cost, low flexibility

- Perplexity: cheaper, simpler, but with more integration overhead

- Custom: full control, but more dev time and maintenance

Failure #5: Skipping visual input in document-based tasks

As humans, we rely on visuals all the time—tables, screenshots, charts, and images often carry more meaning than paragraphs of text. But in our early builds of Omega, the AI couldn’t see any of it. And that created a serious blind spot.

What broke?

When our sales team asked Omega to summarize a pitch deck, extract insights from a case study, or generate a proposal using a PDF, the agent only processed plain text. It ignored tables, missed images, and skipped over visual layouts that were often central to the document’s meaning.

- Tables were flattened or misread, losing structure and meaning.

- Screenshots with embedded text were ignored completely.

- Visual-heavy documents returned summaries that lacked key context or misrepresented the original.

Why it failed

Omega was initially built to process text. But many business documents—especially in sales—contain important information in visuals. Product comparison tables, KPI charts, or pricing summaries often appear as images or structured layouts that plain text parsing can’t capture.

The model didn’t fail because it was inaccurate. It failed because it couldn’t process the kind of content humans often rely on—tables, charts, and images that carry essential context.

How we tried to fix it

We explored three main options for enabling visual and structured data extraction from PDFs:

- Amazon Textract: A fully managed AWS service with high accuracy, especially for complex tables and forms. It requires no infrastructure and integrates easily, but it's costly per page and comes with vendor lock-in risks.

- Open-source stack (pdfplumber + OCR): A DIY approach using pdfplumber for parsing tables and Tesseract for image-based text extraction. It's cheaper and more flexible, but accuracy can vary, and it demands more development effort and maintenance.

- Multimodal LLMs like GPT-4o: The most modern option—feeding entire PDFs directly to a model that can understand text and visuals together. This dramatically simplifies the pipeline and supports complex layouts. But it’s expensive in terms of token usage and less predictable in terms of output consistency.

- Azure AI Document Intelligence: Microsoft’s document processing service that uses OCR and layout analysis to extract text, tables, and key-value pairs from PDFs.

We also considered a hybrid option: converting PDFs to structured Markdown (with table formatting and image metadata), then passing that to a multimodal LLM.

How we solved it

We researched different ways to process a wide range of real-world PDFs. Early on, we tried Azure AI Document Intelligence—and it worked right away.

The results were solid: it preserved table structures, pulled text from images, and handled complex layouts with consistency. Since it fits smoothly into our Azure-based infrastructure, Omega could easily extract structured data and feed it into downstream processes.

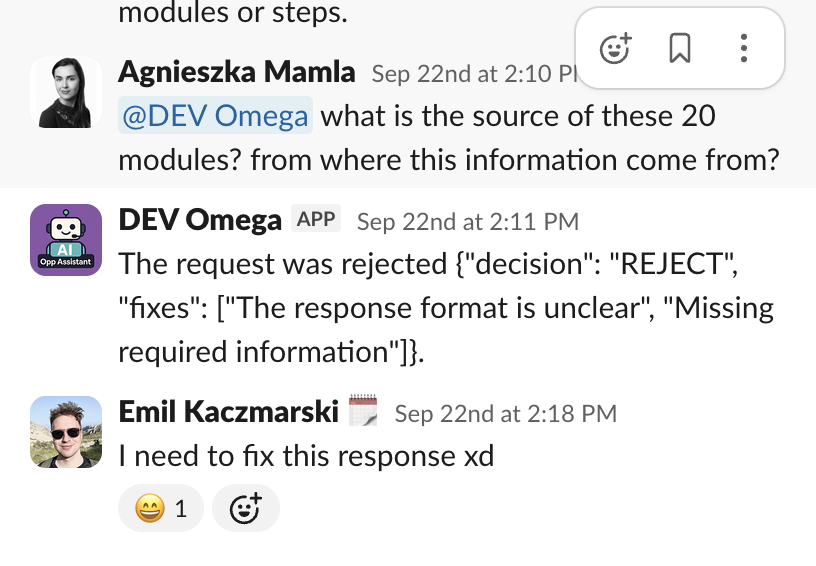

AI Failure #6: Picking a framework before knowing the trade-offs

When you’re building an AI agent system from scratch, choosing the right framework feels like a tactical decision. But in reality, it’s a strategic one. And like any strategy, the wrong call can slow you down months later—just when you need to move fastest.

What broke?

Early on, we needed a way to build and orchestrate multiple AI agents without reinventing everything from scratch. We looked for a flexible, production-ready framework that could grow with our needs. After evaluating several options, we chose AutoGen and used its higher-level API, AgentChat, to accelerate development.

It helped us get the basics up and running—defining agents, assigning roles, and building orchestration flows. But as the system grew more complex, we began to notice limitations that affected customization, model support, and debugging.

Why it failed

We chose AutoGen for its rich ecosystem, Azure integration, and balance between abstraction and control. But that meant we had to accept slower iteration cycles, model support trade-offs, and some vendor-specific limitations.

And while AgentChat helped us move fast early on, it wasn’t built for deep customization or complex, production-grade logic. The more we tried to extend it, the more resistance we hit.

- Limited model support: Some models weren’t supported natively, and updating to newer ones required changes to the AutoGen stack as the model family evolved.

- Reduced flexibility: Customization became harder as more edge cases appeared.

- Opaque debugging: Troubleshooting at the AgentChat level was challenging when processes failed silently under the hood.

What we’re doing now

We’re sticking with AutoGen, but moving deeper into AutoGen Core when we need more control or stability. This lets us retain the benefits of the ecosystem without getting locked into its highest-level abstractions.

We’ve also added fallback strategies:

- Building wrappers around core logic to abstract away from framework-specific dependencies.

- Designing our agents and orchestration flows in a way that could, in theory, be ported to another framework in the future.

- Monitoring emerging alternatives like Google’s ADK (though still too young for production use) for long-term flexibility.

Conclusion: Our AI agent worked because it failed first

Building Omega wasn’t a clean, linear process. At every stage—from infrastructure to orchestration, context limits to visual processing—we ran into friction. Each failure forced us to rethink assumptions and tighten the feedback loop between what we wanted the agent to do and what it was actually capable of.

We learned that:

- Serverless isn’t always the best fit for stateful, multi-step AI logic.

- Dumping raw Slack data into a model just creates noise and hallucinations.

- Too many agents in a flow can lead to infinite loops, token burnout, and zero output.

- A single LLM can’t reason deeply without access to research tools—just like humans.

- Ignoring visuals and structured data means missing the actual story in a document.

- Choosing a framework too early can box you into design decisions that are hard to undo.

In the end, building Omega became its own AI use case—an experiment in what it really takes to create a useful agent. The failures were an integral part of that process, helping us test, compare, and ultimately choose AI solutions that worked.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is Omega and how does it differ from other AI tools?

Omega is Netguru’s internal AI sales agent, built to help sales teams work faster—directly inside Slack. Unlike generic AI chatbots or AI tools, Omega uses a modular, multi-agent architecture to handle real-world tasks like summarizing calls, retrieving documents, and suggesting proposal features—all based on live context. It’s designed to support real-time decision-making without adding new systems to the workflow.

2. What were the biggest technical challenges in building Omega?

We faced several issues that shaped our AI development:

- AI errors like hallucinations due to token limits and raw Slack data.

- Serverless infrastructure (Lambda) not supporting long, multi-agent flows.

- Trouble coordinating multiple agents, which led to loops and burned tokens.

- Framework lock-in and limited flexibility with tools like AutoGen.

- Inability to process visuals (images and tables), which limited understanding of key documents.

These failures were critical learning points that helped us improve Omega’s AI system architecture.

3. How does Omega extract data from documents with images and tables?

Originally, Omega couldn't handle visual elements—key context in sales materials like pitch decks, case studies, or pricing tables was getting lost. We evaluated several solutions and ultimately used Azure AI Document Intelligence. It allowed us to extract data accurately from PDFs, preserving layouts, tables, and even text from images, making it a key part of Omega’s document processing capabilities.

4. How do you prevent incorrect information or hallucinations in AI outputs?

We learned early that dumping raw data (like unfiltered Slack messages) into a model caused hallucinations and incorrect information. To fix this, we built a summarization pipeline, limited context windows, and added retrieval steps from a knowledge base. For deeper answers, Omega is now supported by AI-powered research agents that pull verified information before responding.

5. Is a system like Omega suitable for small businesses?

Omega was built for internal use, but the same approach can work for other companies. With the tech already in place, we can help small businesses implement similar AI systems and autonomous agents to automate tasks and improve efficiency.